Retractions in Scholarly Publishing: Causes, Consequences, and the Path Forward

| Received 01 Sep, 2025 |

Accepted 11 Jan, 2026 |

Published 31 Jan, 2026 |

Retractions play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of the scientific record. While they are often viewed negatively, they represent an essential mechanism for correcting errors, addressing ethical violations, and combating research misconduct. This article explores the common causes of retractions in academic publishing, including data fabrication, plagiarism, authorship disputes, and honest errors. It examines the broader implications of retractions on authors, institutions, journals, and public trust, particularly in fields like medicine, where flawed research can have significant consequences. The article further highlights regional differences in how retractions are handled, noting that practices vary considerably between the Global North and Global South. This disparity underscores the urgent need for harmonized international standards. Drawing on guidelines from the Committee on Publication Ethics and data from Retraction Watch, the article outlines best practices for transparent and ethical retraction handling. It also discusses the growing role of technology and artificial intelligence in detecting problematic research, as well as the need for global collaboration and educational reform. Ultimately, the article argues that, when handled properly, retractions reinforce the self-correcting nature of science and should be seen as indicators of accountability rather than as reflections of failure.

| Copyright © 2026 Negm et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

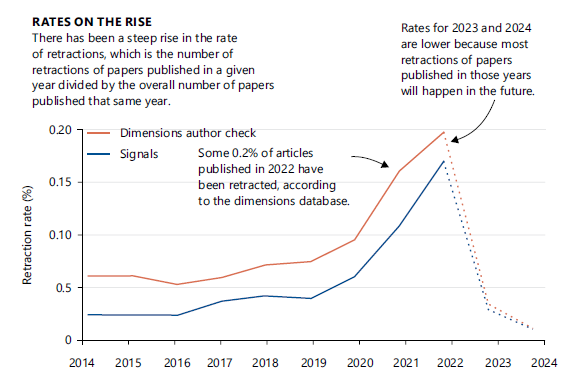

Retraction is the formal withdrawal of a published scientific article from the scholarly record, typically due to errors, ethical violations, or misconduct1. While its purpose is to correct the literature and uphold academic integrity, the process itself often triggers reputational consequences and broader discussions around trust in science2. In recent years, the number of retracted articles has grown significantly, raising concerns across the scholarly publishing ecosystem3. According to Retraction Watch, thousands of papers are retracted annually, with rates accelerating due to heightened scrutiny, digital visibility, and the increased use of misconduct detection tools4.

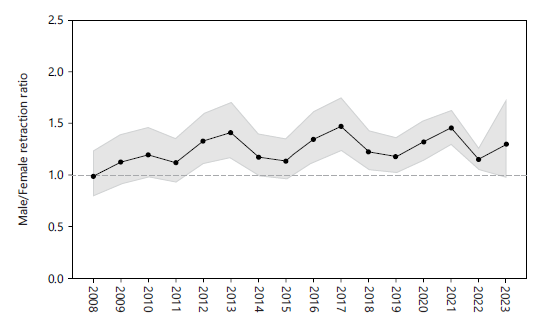

This trend is clearly illustrated in the growing number of annual retractions over the past two decades (Fig. 1).

|

Further, significant geographical disparities exist in research misconduct. A recent 2025 analysis using Scopus data identified the top 100 countries by publication volume from 1996 to 2023 and cross-referenced retraction counts from the Retraction Watch database. Findings revealed that China, the United States, and India account for the highest numbers of retractions linked to misconduct, with China notably overrepresented. These results underscore the urgent need for stronger oversight and enhanced ethical standards worldwide5.

The COVID-19 pandemic further intensified attention on retractions, as several high-profile studies were retracted from leading medical journals. These cases underscored both the dangers of flawed science reaching the public domain and the critical importance of rapid, transparent correction6,7.

Understanding why retractions occur and their significance is vital for editors, researchers, publishers, and policymakers3. Retractions serve as a mechanism for self-correction, but when mishandled or misunderstood, they can exacerbate mistrust, damage careers, and distort the scientific record8. This article explores the multifaceted nature of retractions, their underlying causes, broader implications, and the role of policy and technology in managing them responsibly.

Common reasons for retraction: The reasons behind retractions can be broadly categorized into intentional misconduct, ethical violations, procedural issues, and unintentional errors9.

Research misconduct remains the leading cause. This includes:

| • | Fabrication: Inventing data or results | |

| • | Falsification: Manipulating research materials or processes | |

| • | Plagiarism (including self-plagiarism): Presenting another’s work or ideas without proper attribution or copying or paraphrasing significant portions of one’s own previously published text without proper citation10 |

Retraction watch highlights numerous cases where authors have fabricated datasets or manipulated images to achieve desirable outcomes11. Such actions undermine scientific credibility and are taken seriously by journals and institutions.

| Table 1: | Causes of retractions and their implications | |||

| Cause | Description | Implications |

| Research misconduct | Fabrication, falsification, plagiarism | Severe reputational damage, potential career-ending consequences |

| Ethical violations | Undisclosed conflicts, authorship disputes, and research on unethical study subjects |

Institutional sanctions, loss of trust, policy scrutiny |

| Publication process issues | Duplicate submissions, redundant publication, fake peer reviews |

Editorial burden, compromised peer-review process, and journal credibility loss |

| Honest errors | Methodological flaws, statistical miscalculations, non-reproducibility |

Opportunities for corrections encourage |

| Systemic weaknesses | Weak editorial oversight, lack of training, cultural variance in research ethics |

Highlights need for capacity building, policy reform, and training across global regions |

Ethical violations such as authorship disputes, undeclared conflicts of interest, and breaches in human or animal research ethics also prompt retractions. Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) emphasizes the importance of transparency in author contributions and ethical disclosures9-12,13.

Publication-related issues include duplicate submissions, redundant publications, and manipulation of the peer-review process. Some journals have retracted articles following the discovery of "fake reviewers" - cases where authors suggested fraudulent reviewer identities to influence the peer-review process10-14. Moreover, predatory journals exacerbate this problem by bypassing rigorous editorial checks, thereby further contributing to retractions15.

Honest errors, though less sensational, are equally important16. These include miscalculations, flawed methodologies, or irreproducible results discovered post-publication7. In such cases, retraction is a responsible act rather than a punitive one, and should be viewed as part of science's self-correcting nature17.

In addition, systemic issues such as inadequate editorial oversight, limited statistical literacy among reviewers, and cultural differences in research ethics training contribute to problematic publications. These “latent” causes deserve more attention, as they often set the stage for retractions3-18. Survey evidence confirms that mounting publication pressure is strongly linked to ethical lapses such as paid authorship, plagiarism, and data manipulation factors that ultimately drive retractions. The main causes of retractions, along with their broader implications for the research ecosystem, are summarized in Table 1.

Impact of retractions: Retractions carry a wide range of consequences, affecting not only individual researchers but also institutions, journals, and the broader public19.

On the scientific record, retractions aim to prevent the dissemination of false or misleading information. However, studies have shown that retracted articles often continue to be cited, sometimes without acknowledgement of their retracted status, perpetuating misinformation20. This persistence of “zombie citations” illustrates the need for better integration of retraction metadata into indexing systems like PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar21.

For authors and institutions, retractions can result in reputational damage, loss of funding, academic sanctions, and, in severe cases, legal consequences3. While intentional misconduct warrants such outcomes, honest mistakes should be differentiated and addressed with a supportive approach16,22. There are growing calls for a “taxonomy of responsibility” that distinguishes fraud from error, thereby ensuring proportionate responses23.

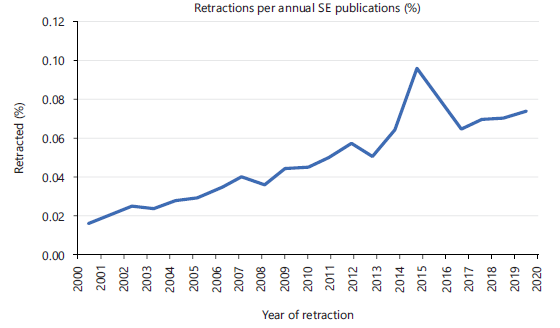

Beyond institutional or professional outcomes, retractions also reveal demographic disparities. Studies indicate that male authors are overrepresented among retracted papers compared to female authors, highlighting systemic patterns that warrant further exploration (Fig. 2).

|

Besides authors and institutes, journals and publishers also bear the brunt of retraction. A rising number of retractions can impact a journal’s credibility, affect its indexing status, and diminish its impact factor.Click or tap here to enter text. Moreover, unclear or delayed handling of retractions can further erode trust. Some publishers now maintain “retraction dashboards” to monitor and analyze trends, helping them identify at-risk areas in their editorial workflows25.

Public trust is perhaps the most fragile. In fields like health and medicine, where research directly informs clinical decisions and public policy, retractions can lead to confusion, mistrust in scientific institutions and the studies they conduct, and reluctance to accept legitimate findings26. The infamous case of the retracted 1998 paper linking vaccines to autism demonstrates how a single fraudulent article can have long-lasting societal consequences, fueling misinformation movements even decades later27.

Current retraction policies and best practices: Clear, consistent, and transparent retraction policies are essential. Journals must establish and publicly communicate guidelines that outline when and how retractions should occur28.

The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) provides detailed recommendations, urging publishers to issue retraction notices that are clearly labeled, linked to the original article, and accessible without restriction. Each notice should clearly explain the reason for the retraction and who initiated it9. Although such guidance exists, studies indicate that retraction notices frequently omit critical information regarding the retraction. In a 2024 study of 441 retracted articles, retraction notice completeness was evaluated using 17 criteria developed by combining retraction notice criteria from COPE and Retraction Watch. Four of these criteria were shared between COPE and Retraction Watch, 3 were exclusive to COPE, and 10 were exclusive to Retraction Watch. Retraction notices were available for 414 (93.9%) of the 441 retracted publications. Among these, only 42.8% (177/414) notices met all 7 COPE criteria, while only 3.4% (14/414) notices satisfied all 7 minimum criteria outlined by Retraction Watch. The findings revealed that retraction notices were often incomplete, with none meeting all established criteria. This lack of completeness remains a persistent issue in practice, ultimately undermining the credibility of scientific publishing29.

Therefore, timely and adequate communication in case of retractions is critical. Delayed retractions allow flawed or unethical research to circulate longer, increasing its impact and citation footprint3. Conversely, premature retractions without due investigation may unfairly penalize authors and undermine the science30.

| Table 2: | Best practices and technological enablers in retraction management | |||

| Best practices (COPE-Informed) | Technological and system-level support |

| Clear, accessible retraction notices that state the reason and authors involved |

Plagiarism detection tools and image forensics for pre- and post-publication review |

| Timely action to reduce the spread of misinformation |

AI-powered anomaly detection and data audits to flag potential issues early |

| Distinguishing between misconduct and honest mistakes |

Blockchain for provenance tracking; standardized metadata schema (e.g., NISO guidance) (Science Editor) |

| Transparent process with public policies | Retraction dashboards and cross-platform indexing with retractionmetadata (e.g., PubMed, Scopus) (publicationethics.org, Science Editor) |

| AI: Artificial intelligence, COPE: Committee on publication ethics and NISO: National information standards organization | |

Examples of best practice include journals that provide detailed retraction notices and collaborate with institutional integrity offices. Additionally, journal editors should verify that all retraction notices conform to the standards set forth by recognized bodies such as COPE and Retraction Watch, thereby ensuring that these notices are comprehensive, transparent, and informative. Poor practices include vague or missing explanations, broken links, or paywalled retraction notices31.

In addition, publishers should invest in proactive integrity checks before publication, such as image forensics and data audits. Retractions should not be seen as the only line of defense, but part of a larger ecosystem of quality assurance.

Best practices in handling retractions, together with the technological enablers that support them, are summarized in Table 2.

Are retractions always bad?: While often viewed negatively, retractions are not inherently bad. In fact, they reflect the scientific community’s commitment to scientific integrity and the self-correcting nature of research7.

Retractions can be a positive indicator when used to correct honest errors or resolve ethical uncertainties32. Encouraging researchers to come forward without fear of unfair punishment helps foster a more open and accountable research culture33.

However, distinguishing between misconduct and honest mistakes is crucial. While fraud must be dealt firmly, unintentional mistakes should be treated as part of the learning and discovery process. Overly punitive responses to honest errors risk discouraging transparency and self-reporting15.

Some experts now advocate for alternative corrective measures, such as “expressions of concern” or “corrections with commentary,” which can help preserve the scientific record while clarifying errors without the stigma associated with full retraction7.

Role of technology and artificial intelligence: Advances in technology are reshaping how potential retraction cases are identified and managed. Tools like plagiarism checkers, image analysis software, and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven platforms can flag inconsistencies, duplicated content, or statistical anomalies before or after publication34. However, reliance on automation introduces ethical and practical concerns. False positives, algorithmic bias, and lack of contextual understanding can lead to unfair scrutiny or unnecessary retractions35.

The AI can facilitate faster, fairer, and more consistent detection of irregularities, but human oversight remains essential. Technology should assist, not replace, the editorial and ethical judgment of trained professionals36,37.

|

Looking ahead, blockchain-based systems for data provenance and AI-driven peer review simulations are emerging as possible innovations that could reduce retractions by identifying issues earlier in the publication pipeline.

Recent analyses underscore the scale of the problem: retraction rates have steadily climbed over the past decade, particularly in medicine and life sciences (Fig. 3). This trend underscores why technological innovations and systemic safeguards are urgently needed.

Strategies to improve retraction handling: To improve the handling and perception of retractions, the following actions are recommended:

| • | For publishers: Establish transparent retraction policies, provide editor training, and collaborate with ethics bodies like COPE | |

| • | For journals: Use plagiarism detection and image integrity tools to catch issues early, encourage corrigenda and errata for minor errors instead of full retractions, provide comprehensive information in retraction notices | |

| • | For editors: Act promptly, maintain neutrality, and ensure clear communication with authors and readers | |

| • | For researchers: Adhere to ethical practices, disclose conflicts, and report honest errors without fear | |

| • | For institutions: Support research integrity offices, provide mandatory training on ethical research practices and publication ethics, protect whistleblowers, and ensure fair investigations | |

| • | Globally: Promote international collaboration to standardize retraction practices and improve awareness across regions and disciplines |

Additionally, funders should play a more active role by linking grant evaluation metrics to research integrity, not just publication counts. Training programs on the responsible conduct of research should also explicitly include case studies on retractions, so that early-career researchers understand both the associated risks and the value of such cases.

CONCLUSION

Retractions are not mere administrative formalities; they are essential to safeguarding the integrity of the scholarly record. When handled with transparency and fairness, they reinforce the academic community’s commitment to self-correction and trustworthiness.

As the volume and complexity of research continue to expand, so too must our ability to address errors and misconduct effectively. Building a stronger and error-free retraction system requires fostering a culture of openness, investing in editorial training, adopting supportive technologies, and establishing global standards.

Ultimately, retractions should not be regarded as a mark of shame but as evidence that science is functioning as intended identifying mistakes, correcting them, and progressing with greater strength. The future of scholarly publishing will depend on whether the stigma surrounding retractions can be transformed into a culture of accountability and learning.

REFERENCES

- Hwang, S.Y., D.K. Yon, S.W. Lee, M.S. Kim and J.Y. Kim et al., 2023. Causes for retraction in the biomedical literature: A systematic review of studies of retraction notices. J. Korean Med. Sci., 38.

- Mattoon, E.R., A. Casadevall and F.C. Fang, 2025. Retractions of COVID-19-related research publications during and after the pandemic. J. Law Med. Ethics, 53: 22-28.

- Khan, R., A. Joshi, K. Kaur, A. Sinhababu and R. Chakravarty, 2024. Retractions in academic publishing: insights from highly ranked global universities. Global Knowl. Mem. Commun..

- Sebo, P. and M. Sebo, 2024. Geographical disparities in research misconduct: Analyzing retraction patterns by country. J. Med. Internet Res., 27.

- Anderson, C., K. Nugent and C. Peterson, 2021. Academic journal retractions and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Primary Care Community Health, 12.

- Furuse, Y., 2024. Characteristics of retracted research papers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Med., 10.

- Joshi, P.B. and S. Minirani, 2024. Retractions as a Bitter Pill Corrective Measure to Eliminate Flawed Science. In: Scientific Publishing Ecosystem, Joshi, P.B., P.P. Churi and M. Pandey (Eds.), Springer Nature, Singapore, ISBN: 978-981-97-4060-4, pp: 307-327.

- Hayashi, M.C.P.I. and J.A.C. Guimarães, 2024. Social dynamics and ethical principles: Keys to reading about retraction in publications. RDBCI: Rev. Digital Biblioteconomia Cienc. Informação, 22.

- Wager, E., V. Barbour, S. Yentis, and S. Kleinert, 2025. Retraction guidelines. COPE.

- Ferguson, C., A. Marcus and I. Oransky, 2014. Publishing: The peer-review scam. Nature, 515: 480-482.

- Banerjee, S., D. Banerjee, D. Pooja, H. Kulhari, H. Jadhav, V.A. Saharan and A. Singh, 2024. Unethical Practices in Research Designs. In: Principles of Research Methodology and Ethics in Pharmaceutical Sciences: An Application Guide for Students and Researchers, Saharan, V.A., H. Kulhari and H.R. Jadhav (Eds.), CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, ISBN: 9781003088226, pp: 47-80.

- Fanelli, D., 2009. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE, 4.

- Balasubramanian, S. and A. Simha, 2024. Peer Review Rings: Manipulated Peer Reviews and Scams. In: Scientific Publishing Ecosystem, Joshi, P.B., P.P. Churi and M. Pandey (Eds.), Springer Nature, Singapore, ISBN: 978-981-97-4060-4, pp: 367-378.

- Sayab, M., 2022. Predatory journals: A new perspective. Trends Scholarly Publ., 1: 11-15.

- Fanelli, D., 2013. Why growing retractions are (mostly) a good sign. PLoS Med., 10.

- Mertkan, S., D. Mills, A. Takir and E.E. Sarıkaya, 2025. Research on retractions: A systematic review and research agenda. Account. Res.

- Heston, T.F., 2023. Statistical ethics in medical research: A narrative review. J. Clin. Med. Res., 4.

- Sayab, M., L.M. DeTora and M. Sarwar, 2025. Publication pressure vs research integrity: Global insights from an Asian Council of Science Editors survey. Sci. Editor, 48.

- Bar-Ilan, J. and G. Halevi, 2017. Post retraction citations in context: A case study. Scientometrics, 113: 547-565.

- Ortega, J.L. and L. Delgado-Quirós, 2024. The indexation of retracted literature in seven principal scholarly databases: A coverage comparison of dimensions, OpenAlex, PubMed, Scilit, Scopus, The Lens and Web of Science. Scientometrics, 129: 3769-3785.

- Joëts, M. and Mignon, V., 2025. Slaying the undead: How long does it take to kill zombie papers? Preprints.

- da Silva, J.A.T. and A. Al-Khatib, 2019. Ending the retraction stigma: Encouraging the reporting of errors in the biomedical record. Res. Ethics, 17: 251-259.

- da Silva, J.A.T., 2022. A synthesis of the formats for correcting erroneous and fraudulent academic literature, and associated challenges. J. Gen. Philos. Sci., 53: 583-599.

- Brainard, J., J. You and D. Bonazzi, 2018. Rethinking retractions: The largest-ever database of retracted articles suggests the burgeoning numbers reflect better oversight, not a crisis in science. Science, 362: 390-393.

- Hosseiniara, S.R., 2024. Impact of publication retractions on researcher and journal metrics: A call for new evaluation formulas. J. Med. Lib. Inf. Sci., 5.

- Curty, R.G., 2025. Managing retractions and their afterlife: A tripartite framework for research datasets. Int. J. Digital Curation, 19.

- Fang, F.C., R.G. Steen and A. Casadevall, 2012. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 109: 17028-17033.

- Khan, H., A.Y. Gasparyan and L. Gupta, 2021. Lessons learned from publicizing and retracting an erroneous hypothesis on the mumps, measles, rubella (MMR) vaccination with unethical implications. J. Korean Med. Sci., 38.

- Bakker, C.J., E.E. Reardon, S.J. Brown, N. Theis-Mahon, S. Schroter, L. Bouter and M.P. Zeegers, 2024. Identification of retracted publications and completeness of retraction notices in public health. J. Clin. Epidemiol., 173.

- Schneider, J., N.D. Woods, R. Proescholdt, H. Burns and K. Howell et al., 2022. Reducing the inadvertent spread of retracted science: Recommendations from the RISRS report. Res. Integrity Peer Rev., 7.

- Srholec, M., 2024. What if your paper were retracted for no credible reason? Res. Eval.

- Wager, E. and P. Williams, 2011. Why and how do journals retract articles? An analysis of Medline retractions 1988-2008. J. Med. Ethics, 37: 567-570.

- Al-Kfairy, M., D. Mustafa, N. Kshetri, M. Insiew and O. Alfandi, 2024. Ethical challenges and solutions of generative AI: An interdisciplinary perspective. Informatics, 11.

- de Peuter, S. and S. Conix, 2023. Fostering a research integrity culture: Actionable advice for institutions. Sci. Public Policy, 50: 133-145.

- Wongvorachan, T., 2025. Rethinking academic publishing: A call for inclusive, transparent, and sustainable reforms. Preprints.

- Horbach, S.P.J.M. and W. Halffman, 2019. The ability of different peer review procedures to flag problematic publications. Scientometrics, 118: 339-373.

- Holzinger, A., K. Zatloukal and H. Müller, 2025. Is human oversight to AI systems still possible? New Biotechnol., 85: 59-62.

- van Noorden, R., 2025. Exclusive: These universities have the most retracted scientific articles. Nature, 638: 596-599.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Negm,

A., Farhan,

S.H., Singh,

R. (2026). Retractions in Scholarly Publishing: Causes, Consequences, and the Path Forward. Trends in Scholarly Publishing, 5(1), 15-22. https://doi.org/10.21124/tsp.2026.15.22

ACS Style

Negm,

A.; Farhan,

S.H.; Singh,

R. Retractions in Scholarly Publishing: Causes, Consequences, and the Path Forward. Trends Schol. Pub 2026, 5, 15-22. https://doi.org/10.21124/tsp.2026.15.22

AMA Style

Negm

A, Farhan

SH, Singh

R. Retractions in Scholarly Publishing: Causes, Consequences, and the Path Forward. Trends in Scholarly Publishing. 2026; 5(1): 15-22. https://doi.org/10.21124/tsp.2026.15.22

Chicago/Turabian Style

Negm, Abdelazim, Sami Hammed Farhan, and Ramandeep Singh.

2026. "Retractions in Scholarly Publishing: Causes, Consequences, and the Path Forward" Trends in Scholarly Publishing 5, no. 1: 15-22. https://doi.org/10.21124/tsp.2026.15.22

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.